TLC Blog

Comments from TLC Regarding the Riverwoods Subdivision

02 April 2024

You can read TLC’s position here.

Can you help? Household items wanted for CLIP program

06 March 2024

TLC is excited to welcome the next crew of interns to the Conservation Leader Internship (CLIP) program! For the first time, this summer, TLC will provide CL…

A Prescribed Burn at Irish Oaks Nature Preserve

06 March 2024

Last week a group of volunteers came out to help with a prescribed burn at Irish Oaks! Prescribed burns are conducted rotationally to mimic what would have o…

Woodstock High School Students Volunteer at Donato Woods

04 March 2024

Thank you to the amazing volunteers from Woodstock High School’s Blue Streak Service Club who helped clear brush at Donato Woods on March 3!

(Photos courtes…

Would you like to help out at TLC’s native plant sale?

22 February 2024

Volunteers are wanted to help out at TLC’s native plant sale May 7-11. Check out the links below to find a date and time that work for you.

Thank you to e…

Meet TLC Board Member Terry Willcockson

26 January 2024

How do you spend your days?

Retirement has been an interesting motivational experiment, following decades of intense daily work and family demands. Zen t…

Meet TLC Board Member Melissa Cooney

26 January 2024

How do you spend your days?

I have lots of hobbies including knitting, needlepoint, and I travel as often as I can.

What are your ties to McHenry Coun…

Meet TLC Board Member Kurt Taylor

25 January 2024

How do you spend your days? (work, volunteering, etc.)

I still work, but I own the company and have time to volunteer and do what I’d like to do most days. …

New Year’s Eve Oak Rescue – Thank You!

02 January 2024

Happy New Year!

Thank you to everyone who celebrated New Year’s Eve with an Oak Rescue at Thompson Road Farm in Bull Valley! This fabulous group…

Refer a Friend and Get a Cool TLC Gift!

13 December 2023

Thank you for being a member of The Land Conservancy of McHenry County!

When you refer a non-member friend to TLC, we will send you your choice of a 2024 …

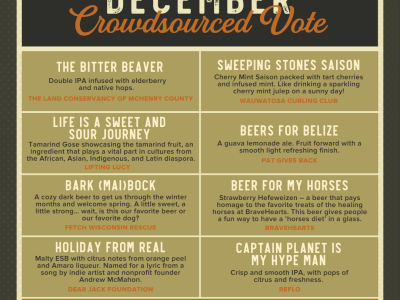

Vote for TLC’s Bitter Beaver Beer in MobCraft Brewing Voting

11 December 2023

Here’s a fun one! MobCraft Beer Woodstock takes votes on crowdsourced beers. TLC has nominated the Bitter Beaver beer, a Double IPA infused with elderberry a…

Closing Out the 2023 Summer Season – CLIP Week 10

14 August 2023

by Joee Cortina

Seeding at Apple Creek

Hello for the last time, and welcome to t…

Environmental careers, nature art and Nachusa – CLIP Week 9!

14 August 2023

by Katie Mikkelson

Monday July 31

We started our day with a career panel where we talked to professionals in the field of ecology. They told us about h…

A Bat, a Food Forest and Hatching Caterpillars – CLIP Week 8

03 August 2023

A bat in a pawpaw tree

Monday we spent the day with Jack and Judy Speer at Small Wa…

Rusty-Patched Bumblebee Sighting at a TLC Site!

01 August 2023

A rusty-patched bumblee was spotted at a TLC site this week! TLC actually has two sites serving as rusty-patched bumblebee habitat. This bee is state and fed…

Finding Black Cohosh, Surveying a Stream and Destroying Turfgrass – CLIP Week 7

26 July 2023

by Emma Klein and Leah Williams

Welcome to week seven of TLC’s 2023 Conservation Leader Internship Program! This week’s update is provided by Emma and Lea…

Parsnip, Parsnip and Rainy Day Activities – CLIP Week 6

26 July 2023

by Joee Cortina

Welcome to week 6 of CLIP! The summer is well underway – as I write this, we just passed over the halfway point of the program! As interns…

A Field Trip to Midewin, Pulling Parsnip and More – CLIP Week 5

14 July 2023

by Nari Coleman

Date: Wednesday, July 5, 2023

Entry: On Wednesday morning, the CLIPsters arrived at Hennen early for a field trip to Midewin National T…

Seeds, Butterflies and Trees – CLIP Week 4!

13 July 2023

by Jenn Hernandez

To start off week 4 of CLIP, Monday didn’t exactly go as planned due to rain forecasted later in the day. Sadly, we couldn’t spray the t…

Monitoring, Planting, and Pulling – CLIP Week 3

06 July 2023

by Kate Mikkelson

Monday 6/19

We started our week with a visit to Pistakee Bay, which is a property that’s owned and managed by TLC. We met with Randy …

A Trip to the Dunes, Learning to Chainsaw and More – CLIP Week 2!

26 June 2023

By Leah Williams

Welcome to the second week of CLIP! This week all the interns picked up a ton of new skills, as we visited everywhere from Irish Oaks and…

CLIP 2023 is Underway!

16 June 2023

by Emma Klein

Welcome to the first week of TLC’s 2023 Conservation Leader Internship Program! This week’s update is provided by CLIP’s 2023 crew leader, E…

Learning about Our Local Native Wildflowers

08 May 2023

We had a great group of people at the Wildflower Walk on Saturday, May 6 at Spring Hollow in Woodstock! Thank you to all who attended and learned about our n…

TLC’s Latest Conservation@Home Yard Certification – Jermaine Burney

02 May 2023

Congratulations to Jermaine Burney on his Conservation@Home yard certification! A new oak landowner in Crystal Lake, he reached out to TLC for advice on cari…

TLC’s 32nd Annual Celebration – A Recap

28 April 2023

TLC’s 32nd Annual Celebration took place on Sunday, April 23.

Guests had a pleasant afternoon at a new venue, the McHenry Country Club and enjoyed a “high t…

Identifying Trees in Winter

24 January 2023

TLC’s Winter Tree and Shrub Identification class took place Jan. 18 at Ryders Woods. We learned how to identify several native trees and shrubs as well as so…

Job Opening at TLC – Food Forest Manager

09 January 2023

Food Forest Manager (part time) View PDF job description

The Land Conservancy is looking for the right person to help us with our food forest! Our goal i…

TLC’s Farm Program – Year in Review

06 January 2023

Last year was a busy year for TLC’s farm programs! Watch this video to see some of the highlights from 2022.

Summer Position – Seasonal Restoration Technician

05 January 2023

The Land Conservancy of McHenry County is hiring a Seasonal Restoration Technician for the Summer of 2023.

Position title “Seasonal Restoration Tech”

May…

TLC Hosts New Year’s Eve Oak Rescue

05 January 2023

On New Year’s Eve, TLC hosted another successful McHenry County oak rescue! Thanks to the wonderful crew who worked at Irish Oaks Nature Preserve to free two…

CLIP Class of ’22 Research Report

24 August 2022

The CLIP Class of ’22 put their knowledge and skills to work by putting together a research report on germination rates of Rudbeckia triloba after garlon che…

A Fond Farewell to TLC’s CLIP Interns – CLIP Week 11

18 August 2022

(Casper) Monday:

Since it was raining today, we read and discussed our last assignment. Then we worked on making a map of all the locations we have gone …

Bison, native plant gardens, first aid and more – CLIP Week 10

11 August 2022

by Breanna Christensen

To begin the week we spent Monday morning meeting on Zoom for a Conservation Career Panel. We met with multiple people CLIP Directo…

A visit to MCC, loads of toads and more – CLIP Week 9

01 August 2022

by Gretchen Casper

On Monday, we had a work day around Hennen Conservation Area in Woodstock. We started by planting nine flats of plants donated from Red…

Field work, fungus fun and more – CLIP Week 8

01 August 2022

by Amelia Swiecki

Week 8 of CLIP was packed full of invasive work, collecting mushrooms, and working with some great people out in the field!

We kicke…

Lots of work, lots of fun and lots of teasel – CLIP week 7

19 July 2022

by Isaac Servin

This week was great; we got to get some work done obviously, but there were also some really fun activities and we met a couple new faces…

A visit to Midewin Tallgrass Prairie, pulling parsnip, jumping spiders and more! CLIP week 6

12 July 2022

by Kristi Robinson, CLIP lead intern

After the day off on Monday, July 4, we kicked off our 6th week of CLIP on Tuesday with a morning of parsnip pulling …

Finding rare plants, removing invasives, and more! CLIP week 5

08 July 2022

by Breanna Christensen

Monday morning of CLIP’s week 5 was spent with Bruce Kessler, McHenry County restoration expert, at the Tauck Conservation Easement…

Dunes, a farm, kittens and more! An overview of CLIP Week 4

05 July 2022

by Gretchen Casper

On Monday we went to Glacial Park Conservation Area, and met with Sarah Michehl, TLC’s community engagement specialist. She talked to u…

Chainsawing, stream surveying and more! CLIP Week 3

22 June 2022

by Amelia Swiecki

To kick off Week 3 of CLIP, we all headed out to Bluestem Ecological Services, a native plant landscaping company in Marengo. We began o…

Planting a pollinator garden and much more! CLIP Week 2

14 June 2022

Welcome to Blog #2 of TLC’s internship program. This week it is brought to you by Isaac! He is one of the interns this year, and this week there was a lot of…

Happy June! TLC’s CLIP Week 1 is underway

06 June 2022

Welcome to Blog #1 of TLC’s 2022 Conservation Leader Internship Program! This first week’s blog is brought to you by Kristi, CLIP’s Crew Leader for the 2022 …

Welcome 2022 CLIP interns!

02 June 2022

On June 1 TLC welcomed four new interns (and welcomed back a Crew Leader) to the Conservation Leader Internship Program (CLIP) for 2022. We are excited to ha…

CLIP Wish List

31 May 2022

As a nonprofit organization, TLC relies on the generosity of donors for the success of many of our programs. The CLIP team has created a wish list to help en…

Claire Hodge joins TLC as new farm program assistant

02 May 2022

TLC is happy to welcome local farmer Claire Hodge to the team as the farm program assitant. Claire will develop TLC’s Women’s Learning Circle program through…

Welcome Karen Lavin to the TLC Board

18 April 2022

Karen has lived in Wonder Lake, IL most of her life. She was an attorney for 35 years and is now retired. She has fond memories of growing up on a lake – whe…

Planning a Pollinator Garden for the Community

13 April 2022

On April 12 the Youth and Family Center of McHenry County Conversacion de Conservacion Small Waters Education and Friends of Hackmatack National Wildlife…

Christine Nye Joins TLC Board of Directors

01 April 2022

Christine is one of three people who were elected to the TLC Board of Directors in January. Christine has had a lifelong relationship with the land in McHenr…

The Dance of the Woodcock with McHenry County Audubon

24 February 2022

Spring is here! Join us to watch American Woodcocks performing their amazing courtship flights. The male woodcocks will make several preent calls and then la…

Mark Newton Joins TLC Board of Directors

17 February 2022

Mark is one of three people who were elected to the TLC Board of Directors in January. He is a Village of Bull Valley trustee and has a certificate in ecolog…

Farmland Conservation Easements 101 Video

01 February 2022

Do you own or hope to own farmland, or know someone who does? Learn about agricultural conservation easements, what they can offer for your farmland, or how …

New videos posted on a variety of conservation topics

24 January 2022

Have you ever wondered how to start a native plant garden, use a rain barrel or get rid of buckthorn? Check out some of the videos we have posted on these an…

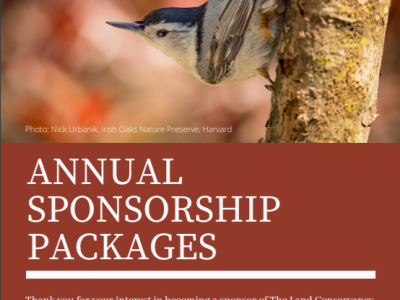

Become an Annual Business Supporter of TLC in 2022!

12 January 2022

If you are a business or organization that values the natural beauty and rural character of McHenry County and wants to make sure it remains that way, consid…

Look out buckthorn and honeysuckle! Grant helps TLC increase stewardship capacity

05 January 2022

In 2017, through the advocacy of the Prairie State Conservation Coalition, Illinois Environmental Council, TLC and dozens of nonprofit conservation land trus…

A great day for an Oak Rescue

03 January 2022

TLC hosted an Oak Rescue on New Year’s Eve at Crowley Oaks Woods in Harvard.

What is an oak rescue? It’s an opportunity for people to work together to fre…

An Eagle Scout project update

03 November 2021

Jack Newton led Boy Scout Troop 149 in building a bridge at TLC’s Boloria Meadows in September for his Eagle Scout project. In addition, the bridge on the le…

TLC holds special workday in honor of Al Van Maren

01 November 2021

TLC dedicated a workday to our friend, the late Al Van Maren on Sunday, Oct. 31. Friends and family of Al Van Maren spent time clearing brush in his oak wood…

Why share native plant seed?

25 October 2021

Each fall TLC hosts a native plant Seed Sharing Day in McHenry County. Sharing native plant seeds with others is a great way to get more native plants growin…

Attracting Hummingbirds – A Fun Family Activity

16 September 2021

by Julio Cardona

Hummingbirds are the smallest birds in the world, and they’re quite an impressive sight when they flock to your backyard. If you’re looki…

The final week: A roundup of CLIP week 11

16 August 2021

Monday: by Arden Podpora

The crew at the TLC office

Our last week started with r…

Sawing logs and seeing bison: A roundup of CLIP week 10

16 August 2021

by Sofia Oropeza

Chainsaw practice

Monday always brings the start of a busy week…

Creek chubs to chainsaws: A roundup of CLIP Week 9

03 August 2021

by Claire Gregory

It’s hard to believe that nine weeks have already passed since the CLIPterns joined the TLC team, but each day is still an adventure.

…

Seeds for the future: A roundup of CLIP Week 8

30 July 2021

by Kristi Robinson

Though I was gone last week for a drum major camp, I was excited and ready to be back at TLC for week 8 of our CLIP internship!

We …

The Illinois Prairie: A Roundup of CLIP Week 7

23 July 2021

by Arden Podpora

With more than half of the summer already gone, our time with CLIP has been flying by. Even though we had a reduced crew of just two inte…

Each day is a new adventure: CLIP Week 6

20 July 2021

By Evelyn Bustos

Week 6 of the CLIP internship had many unique experiences and learning opportunities, from understanding forest pests to monitoring Plant…

Into the Open Arms of Nature: A Roundup of CLIP Week 5

08 July 2021

by Sofia Oropeza

So much mullen!

Last week we were welcomed into the open arms o…

The Art of Restoration: A Roundup of CLIP Week 4

28 June 2021

Testing plant identification skills

by Claire Gregory

Week 4 brought the first f…

Cherries, Berries and Prairies: A Roundup of CLIP Week 3

23 June 2021

by Kristi Robinson

Hi! I’m Kristi, one of the CLIPterns, and I’ll be leading you through a recap of this past week.

[caption id=”attachment_5669″ alig…

From Butterflies to Brush Saws: A Roundup of CLIP Week 2

15 June 2021

by Arden Podpora

The second week of TLC’s internship program, CLIP, was no less eventful than the first. From butterflies to brush saws, we gained valuabl…

Let the summer begin! TLC’s CLIP program is underway

08 June 2021

Last week TLC launched its CLIP internship program, which is designed to be a hands-on learning experience designed to empower participants with the knowledg…

Learning about McHenry County’s Vernal Pools

27 April 2021

Those who attended the vernal pool hike on April 24 were treated to a beautiful hike and lots of tadpoles as well as other tiny creatures!

Vernal pool…

Blanding’s Turtle found on a TLC site

12 April 2021

TLC staff found a Blanding’s Turtle on a TLC site. The turtle appears to have suffered (and healed) from a past injury. Blanding’s turtles are considered end…

Build Your Own Birdhouse for Your Backyard Birding Hobby

12 February 2021

Throughout 2020, social distancing considerably limited our options for entertainment and hobbies. Sheltering-in-place has definitely expanded our appreciati…

TLC Celebrates 200th Conservation@Home Property

30 September 2020

Congrats to Carol Giammattei on becoming TLC’s 200th participating Conservation@Home property!

Not only is Carol a dedicated TLC volunteer, she’s also lan…

TLC Office Hours

28 September 2020

Need to stop by or call the TLC office in Woodstock? Our office hours for the next few weeks will be Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday from 1:00-5:00 p.m.

Splendor in the Grass

31 August 2020

After traveling 6,000 miles from Argentina, you make a stop in Alden, Illinois.

You are a bobolink, one of the most traveled migratory songbirds in the worl…

Piscasaw Gardens blossoms at new location

01 July 2020

Sonja and Rich Brook have built a legacy on their farm in rural Harvard. People who frequent the Woodstock Farmers Market know the Brooks for their flavored …

TLC Completes Its Largest Land Acquisition

30 June 2020

I hope Phase 4 of Illinois’ coronavirus reopening finds you and your loved ones well, and that you are managing with any changes you’ve experienced through t…

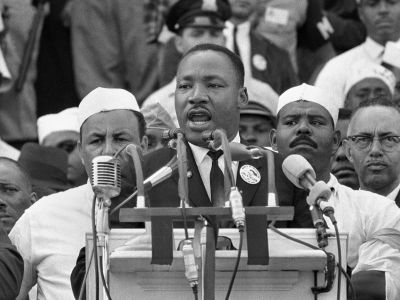

Taking Care to be Anti-Racist

11 June 2020

The same month that I was born, August 1963, was when Martin Luther King Jr gave his “I have a dream speech,” in which he said he dreamed of a day when his “…

TLC reaches milestone in 5000 Acre Challenge

03 June 2020

The Land Conservancy of McHenry County is pleased to announce that since the launch of the 5000 Acre Challenge in late January, private landowners and munici…

Best Ways to Preserve Nature While Hiking

20 April 2020

There are a lot of reasons why hiking is one of the most popular outdoor sports. It’s easy to do, and almost anyone can do it. There’s no need for a lot of e…

A note from Lisa Haderlein

17 March 2020

Dear Friend of TLC, On this beautiful day (March 17), I wanted to reach out and wish you and yours the best of health. Try to enjoy this pause as th…

Residents Join The Land Conservancy of McHenry County’s 5,000 Acre Challenge to Protect Oak Woods

13 March 2020

51 new acres of oak woods added since January The Land Conservancy of McHenry County (TLC) has partnered with local landowners and donors to care for 51 ne…

A look back at what TLC volunteers accomplished in 2019

10 March 2020

The Land Conservancy was looking to create a fun and meaningful way to look back on all the work we’ve been able to do with our volunteers over the last year…

Video: A look at TLC’s accomplishments in agriculture in 2019

16 January 2020

As we look back on 2019, we thank Food:Land:Opportunity for their generous support of our work to promote local food farmers and regenerative farming in McHe…

TLC Preserves 83 Acres of Wetland, Sedge Meadow and Wet Prairie in Woodstock

27 December 2019

The Land Conservancy of McHenry County (TLC) has preserved an 83-acre property, Slough Creek Wetland Bank, located northwest of Woodstock on Jankowski Road. …

Hawk release at Wolf Oak Woods

06 December 2019

Earlier this fall a young red-tailed hawk was found at Wolf Oak Woods that had likely been clipped by a car. She had a concussion and other injuries. Staff f…

Meet TLC Volunteer Mary Mariutto

04 November 2019

The best ideas surface when friends meet new friends over coffee. In 2008, Rene Dankert invited me to meet Lisa Haderlein and Linda Balek for coffee and brai…

In Memory of Lynn Pensinger

05 September 2019

TLC member and friend Lynn Pensinger passed away on Sept. 1. In 2009 the Pensingers protected their three-acre Woodstock property with a conservation easem…

TLC Receives National Recognition

29 August 2019

In August, TLC was accredited by the Land Trust Accreditation Commission. To become accredited, TLC provided extensive documentation and was subject to a co…

The Nature of Flooding will keep changing

31 May 2019

If it seems that rain events are more intense and frequent than they used to be, it’s because they are. Precipitation patterns absolutely have changed ove…

Meet TLC Volunteer Carol Giammattei

12 April 2019

How (and when) did you start volunteering for TLC? I read a newspaper article about an Oak Rescue being held at Yonder Prairie in Woodstock with The Land …

Meet June Keibler, one of TLC’s new board members

28 February 2019

June Keibler returns to TLC’s board of directors in 2019 after serving on the board from 1991-96. She and her husband Steve live in Dundee and have a grown …

In Memory of Becky Walkington

18 January 2019

Becky Walkington, daughter of Dick & Betty Babcock, passed away Jan. 16, 2018 after a struggle with cancer. Becky continued the stewardship of Spring Hol…

An Arborist’s Perspective on Tree Care

01 November 2018

Many people tell me they don’t think that trees need care or attention. They think that trees in the woods don’t need help to survive, so they don’t do anyth…

Want to Protect Woodlands, Prairies and Wetlands? Vote.

02 October 2018

I received this article from Jessica Campbell and Lois Johnson of the McHenry County chapter of the Citizens’ Climate Lobby and would like to share it with y…

Oak Care in Cold Weather

04 September 2018

Tree Tips by Davey Tree Expert Company Summer is drawing to a close and fall is near. The oaks are getting ready to put on their fall show and go int…

Purple Milkweed Exists …

20 July 2018

in McHenry County! This purple This purple milkweed was found at a high-qualty natural area near Woodstock. It’s different from common milkweed …

Let the Sun Shine In

20 July 2018

If you drive along Illinois Route 120 between Woodstock and McHenry, you have surely seen the Wolf Oak Woods property. This is the site where “that oak” live…

Happy Valentine’s Day

11 February 2018

What do you associate with Valentine’s Day? Hearts and flowers? A box of chocolates? Valentine’s Day cards? Birds? In the fifth century A.D., Pope Galesius e…